Margaret Bourke-White

1904-1971

About

Margaret Bourke-White lived the life most of us only dream about. Well, maybe only photographers dream about. But to live life as fully as she did, could only inspire the un-inspirable.

She was born on June 14th, 1904 in the Bronx, New York to Joseph and Minnie Bourke-White. She was one of three children. Joseph White was an engineer who worked with printing presses and the development of offset lithography and the rotarypress. Margaret remembers him as “the personification of the absent-minded inventor. I ate with him in restaurants where he left his meal untouched and drew sketches on the tablecloth. At home he sat silent in his big chair, his thoughts traveling, I suppose, through some intricate mesh of gears and camshafts. If someone spoke he did not hear.” Her mother was educated at Pratt Institute in stenography and was a dedicated homemaker who encouraged her children to become educated. When Minnie would discover that one of her children had a new found interest, she would leave books around the house pertaining to that subject.

Her mother gave her the belief that life was sacred and her father, although “abnormally silent”, gave her a lust and fearlessness of life. As a young girl Margaret was interested in insects, turtles, frogs, books and maps. So much that originally she wanted to be a Herpetologist. In her book Portrait of Myself, she writes, “I pictured myself as the scientist, going to the jungle, bringing back specimens for natural history museums and doing all the things that women never do”. On the rare occasion her father would leave his drafting tools, he would visit the factories where his inventions were put to work. Of course, Margaret would want to come along. “One day, in a plant in Dunellen, New Jersey, I saw a foundry for the first time. I remember climbing with him to a sooty balcony and looking down into the mysterious depths below. “Wait,” Father said, and then in a rush the blackness was broken by a sudden magic of flowing metal and flying sparks. I can hardly describe my joy. To me at that age, the foundry represented the beginning and end of all beauty.”

Although her father was very fond of photography and was always experimenting with lenses and other gadgetry, Margaret did not pick up a camera until after her father’s death. In 1921, Margaret had enrolled in classes at Columbia University in New York to study art. Her mother bought Margaret her first camera that year. It was a 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ Ica Reflex. The camera had cost her mother $20 and it had a cracked lens. She took a one-week course under Clarence H. White. She chose the course because it dealt with design and composition; she didn’t take it because she wanted to make photographs. However, it planted a seed. Later that year she transferred to the University of Michigan. She met Everett “Chappie” Chapman who would later become her husband. Throughout her college career, Bourke-White attended 7 Universities and studied art, swimming and aesthetic dancing, herpetology, paleontology and zoology. At her final university, Cornell, she had a difficult time finding a job. She had an idea to photograph the campus and sell the images. After making arrangements with a commercial photographer to use his darkroom, Bourke-White made her first step to become a photographer.

Her photographs were a huge success. Calls began to come in from architects wondering if she was studying to become a photographer, which had never crossed her mind until that point. She took her portfolio to York & Sawyer, a large architectural firm to hear an unbiased opinion of her work. Margaret Bourke-White left the office with confidence as he told her she could walk into any architectural office and receive work. Her marriage to Chappie had ended just after a few years, and now Margaret had the freedom to “embark on my new life”. After her divorce Margaret assumed her maiden name, but added the hyphen to officially become Margaret Bourke-White.

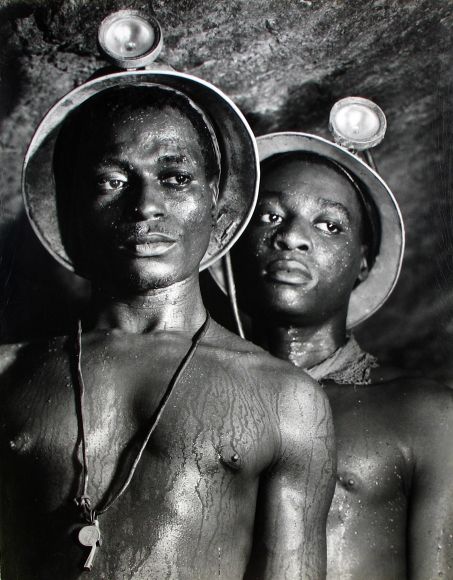

The beauty and lore of industry, which Bourke-White had seen as a child were reignited when she moved to Cleveland. Her photographs of the Otis Steel Mills began her career as an industrial photographer. She sold them for $100 each. Bourke-White’s first studio was in one of Cleveland’s latest skyscrapers. Although it was not her goal, she became one of the pioneers of industrial photography. Years later she would have the first cover to Life magazine, depicting the industrial age. However, her first magazine job came with Fortune, who sought her vigorously. She did not want to relocate to New York because the studio in Cleveland was very successful. The magazine settled for a part-time contract of $12,000 per year. It quickly became one of the leading photographic magazines and gained Bourke-White even more recognition. She was commissioned to document the building of the Chrysler building, which in 1930 became the new home of her second studio. The 61st floor gave Bourke-White access to the jutting gargoyles and perfectly dangerous imagery. Also in 1930, Bourke-White became the first foreign photographer to have unlimited access to the Soviet Union. In a 1935 poll she was named one of the 20 most notable American women, and in 1936, was named one of ten. 1936 also marked a changed in her career.

While working in the Soviet Union recording the industrialization, Margaret began to notice the people. Although she was not equipped emotionally to record their lives, it lay the ground work for future images. Margaret had a dream that all of the cars she was photographing turned on her with hoods snapping as if to swallow her. She vowed from then, “for the rest of my life, I would undertake only those photographic assignments which I felt could be done in a creative and constructive way”. Her turn to social documentary led her to Erskine Caldwell, the author of Tobacco Road.

Erskine Caldwell was looking for a photographer to accompany him on a trip to the South where he was going to write a second book. As a strong, independent woman working by herself, Margaret was not quite ready to accept orders. Almost as soon as the trip began, Caldwell called it off because the two were not getting along. However, the book was important to Margaret and she needed it for her career and she was willing to do anything. The result was You Have Seen Their Faces, which was published in 1937. In the meantime, Life magazine had begun to form and Margaret was one of the first photographers to be called. Her first assignment was to cover the Public Works Administration dam project in Montana. When and if it would run in the magazine was unclear, until the negatives arrived 24 hours before the first issue was to be released. Her photographs were not only the cover and cover story, but the first true photo essay. “Her influence on all of us was incalculable. It was from her that I learned to worship the quality of a photographic print. Day after day I watched her mark up pictures and send them back for reprinting until they met her standards” wrote photographer Carl Mydans. She set the standard for photojournalism and quality.

Although Margaret had vowed to never fall in love again after her horrible marriage with Chappie, Erskine Caldwell somehow caught her off guard and the two fell in love while on their trip to the South. They moved to a New York apartment, but Margaret was busy with her assignments with Life. They produced another book together, North of the Danube. It covered Czechoslovakia and how it was coming under the reign of the Nazis. By this time Caldwell wanted Margaret to marry him, but she would not agree. She wrote in her autobiography, “It is often said that a woman is most strongly drawn to the man who needs her the most. I had always considered myself too selfish to be governed by such a motive. But there must be something to it.” And with that, they were finally married in February 1939. She continued to travel with Life, but soon after her marriage the magazine was printing very few of her photographs and her husband wanted her home. PM was a new New York newspaper that wanted Bourke-White’s imagery and she agreed to go to work for them. It was short-lived. Although she was able to photograph different subject matter for the newspaper, flowers, insects and animals, a daily newspaper could not handle her insistence on quality images and she was soon back with Life.

In 1941, Caldwell and Bourke-White went to the Soviet Union. With 5 cameras, 22 lenses, 4 developing tanks and 3,000 flashbulbs, her luggage total was 600 pounds. But it paid off; she was the only photographer in Moscow during the German raid on the Kremlin and she photographed Josef Stalin. Upon their return to New York, Caldwell was pressuring Margaret to have a child. Although Margaret secretly wanted a child, her independence and her career were more important. Soon after their return Life was calling Margaret back to England to photograph the American B-17 bombers headed for war. Caldwell asked for a divorce.

Bourke-White requested permission to cover the North African campaign and she was sent by ship. Just one day off the African coast in the middle of the night, the ship was hit by a torpedo. The ship sunk and she and just one of her cameras, the Rolleiflex made it to the lifeboat. The only lesson learned from the sunken ship was to carry less equipment, as the next assignment was to fly a bombing raid in a B-17. The photographs she took from this assignment we run in the March 1 issue of Life. It included a photograph of her just before she flew, dressed in all of the appropriate flying gear. Amazingly, this photograph became one of the Army’s favorite pin-up posters. “It was the most over-dressed pin-up in the history of the war” (Vicki Goldberg). She covered almost the entire war and after the German’s surrendered she wrote Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly. It was a book “saturated with her anger, her hatred of Germany, her commitment to democratic ideas, and her despair over American indifference to the moral implications of the war” (Vicky Goldberg).

One of Margaret Bourke-White’s most famous images was taken of Gandhi with his spinning wheel in 1946. There were two conditions: do not speak to him (it was his day of silence) and do not use artificial light. As she peered into his hut, she saw that it was obviously too dark. She convinced them to let her use 3 bulbs. She recounts the day, “I was grateful that he would not speak to me, for I could see it would take all the attention I had to overcome the halation from the wretched window just over his head. He started to spin, beautifully, rhythmically and with a fine nimble hand. I set off the first of three flashbulbs. It was quite plain from the span of time from the click of the shutter to flash of the bulb that my equipment was not synchronizing properly. The heat and moisture of India had affected all my equipment; nothing seemed to work. I decided to hoard my two remaining flashbulbs, and take a few time exposures. But this I had to abandon when my tripod “froze” with one leg at its minimum and two at their maximum length. Before risking the second flashbulb, I checked the apparatus with the utmost care. When Gandhi made a most beautiful movement as he drew the thread, I pushed the trigger and was reassured by the sound that everything had worked properly. Then I noticed that I had forgotten to pull the slide. I hazarded the third peanut flash, and it worked. I threw my arms around the rebellious equipment and stumbled out into daylight.” Bourke-White stayed in India for 2 years to record the people, places and social structure. She was then off to cover the Korean War.

During the Korean War, Margaret started noticing the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. By 1957 she was unable to continue her photography and her work for Life. While living with her disease she wrote her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, lectured, and several essays about her life. She also endured two brain surgeries in the hopes that the symptoms of Parkinson’s would be alleviated, but they were unsuccessful. She died in Connecticut at the Stamford Hospital on August 27, 1971.

These photographs are just a few of the thousands that represent her life-long body of work. She photographed the likes of Winston Churchill, Roosevelt, Pope Pius XII, but also brought home the horrors of war and the people it affects. The photographs she took of the emerging industrial age speak not only to world history, but also to movements in the history of photography. She pioneered quality photojournalism and the photo essay, and published 11 books.

Margaret Bourke-White once wrote, “in this experience of mine, there was one continuing marvel: the precision timing running through it all…by some special graciousness of fate I am deposited—as all good photographers like to be—in the right place at the right time”.

By Lori Oden For IPHF