Joe Rosenthal

About

Though the career of Joe Rosenthal spanned more than 50 years, he is best known for a single image: Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima. The photograph of six men on a tiny island in the Pacific was immediately a symbol of victory and heroism, and became one of the most famous, most reproduced and even most controversial photographs of all time.

(1911-2006)

Photo Credit: HOF Inductee: ©Joe Rosenthal - Flag Raising on Iwo Jima, 1945

Rosenthal was born October 9, 1911 in Washington D.C. to Russian Jewish immigrants. During the Great Depression, he traveled to San Francisco to live with his brother and look for work. He developed an interest in photography, and his hobby soon led to employment as a reporter photographer for the Newspaper Enterprise Association.

At the onset of World War II, Rosenthal applied to join the U.S. Army as a military photographer. He was rejected by the military because of his poor eyesight, but was eventually assigned by the Associated Press to cover the war in the Pacific. He quickly distinguished himself as an outstanding battlefield photographer in arenas including New Guinea, Guam and Angaur before landing on Iwo Jima with the first wave of Marines on February 19, 1945.

Rosenthal used his bulky Speed Graphic, the standard camera for press photographers of the day, to record dramatic photos of the beach landing while he dodged enemy fire alongside the troops. Four days later, after suffering terrible losses on the battlefield, a platoon of 40 men were sent to secure Mount Suribachi, a volcano and Japanese stronghold located at the southern tip of the island. Upon reaching the summit, a small American flag was raised, the first foreign flag ever to fly over Japanese soil. The historic event was documented by Sgt. Lou Lowery, who shot both posed and unposed photos of the men and the flag for Leatherneck magazine while thousands of Marines and Navy corpsmen cheered from below.

Rosenthal had learned that a flag was to be raised on Suribachi, but he and two other photographers arrived too late to record the event. Upon arrival at the summit, however, they saw that a second, much larger flag was about to be raised. Since he was only five-foot-five inches tall, Rosenthal stacked stones and a sandbag to stand on in order to improve the shooting angle from his vantage point. Using a shutter speed of 1/400 and an aperture of about f.11, Rosenthal photographed the six Marines and one Navy corpsman struggling to plant the huge flag in the rocky ground. Unsure if he had recorded a useable image, he then posed the flag raisers, grouped under the flag in what Rosenthal described as a “gung-ho” picture. Except for the three photographers and the men who had raised the second flag, few paid attention to the proceedings. In the view of the men on the battlefield, the first flag-raising was historically significant, not the replacement, and the battle for control of the island continued.

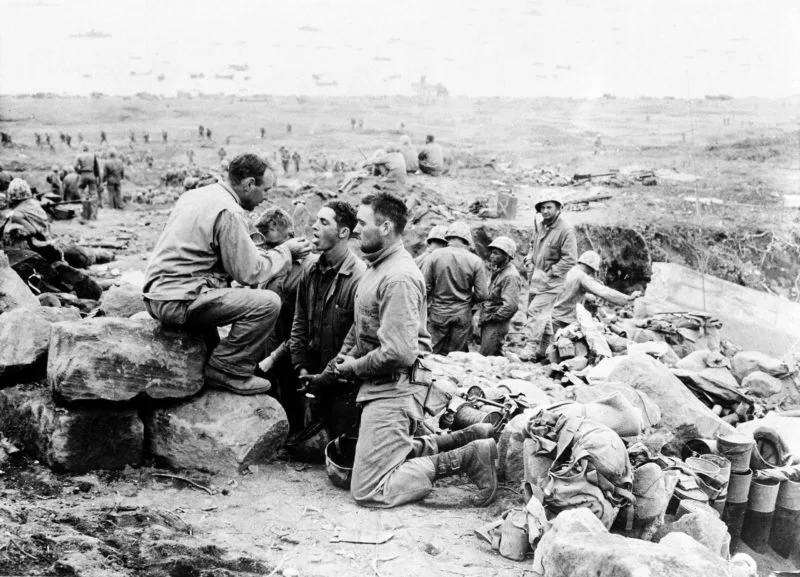

©Joe Rosenthal - U.S. Marines receive communion from a Marine chaplain on Iwo Jima, the largest of the Japanese Volcano Islands, 1945

Rosenthal returned to the command ship and as usual wrote captions for the photos he had taken that day. For the flag raising photos, he wrote, “Atop 550-foot Suribachi Yama, the volcano at the southwest tip of Iwo Jima, Marines of the Second Battalion, 28th Regiment, Fifth Division, hoist the Stars and Stripes, signaling the capture of this key position.” The film was then shipped to the military press center in Guam where it was processed, edited and transmitted via radio to the mainland. It arrived in time to be on the front pages of Sunday newspapers across the country. He was quickly wired a congratulatory note from Associated Press headquarters in New York, but initially Rosenthal had no idea which of his pictures had created such a sensation. He simply assumed it was the posed “gung-ho” image, and when someone asked if the photo had been posed, he answered, “Sure.”

The photograph appeared almost immediately in retail store windows, movie theaters, banks, factories, railroad stations and billboards. The men who raised the flag in Rosenthal’s photograph were ordered home and were treated to a hero’s welcome, but only three had survived. President Franklin Roosevelt made the photograph the theme for the Seventh War Bond Tour, which raised $26 billion for the U.S. Treasury, more than any other bond tour. Just five months after the flag-raising, a stamp commemorating the photograph was issued, even though U.S. law prohibits images of living people on stamps. The photograph won the Pulitzer Prize in 1945, and was the model for the 110-feet tall bronze Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia. Lowery’s photograph, along with the men who raised the first flag, were virtually forgotten. The final American casualties from the battle were recorded as 6,621 dead and more than 19,000 wounded.

After the war Rosenthal joined the San Francisco Chronicle, where he worked for 35 years before his retirement in 1981. Rosenthal was named an honorary Marine in 1996 by then Commandant of the Marine Corps General Charles C. Krulak. Reporters interviewed him extensively after September 11, 2001, when a photograph similar to Rosenthal’s was taken depicting the raising of the flag by three firefighters at the World Trade Center.

Throughout his life, Rosenthal continued to battle the rumor that he somehow staged the flag-raising picture or misrepresented the photo as the first flag-raising. He repeatedly explained that he posed only the “gung-ho” photograph, and denied any deception on his part. Most available historic evidence supports his assertions. Eddie Adams, another former AP photographer, explained, “It has every element…It has everything. It’s perfect: The position, the body language…You couldn’t set anything up like this — it’s just so perfect.”

In spite of the fame that came with the photograph, Rosenthal made little money from it. He received a $4,200 bonus in war bonds from the AP, a $1,000 prize from a camera magazine, and about $700 for a few radio interviews. His name does not appear on the Marine Corps statue until 1982.

Following his death in 2006 at the age of 94, he was awarded the Department of the Navy Distinguished Public Service Award by the Marine Corps. The Hollywood film Flags of Our Fathers recounts the story behind the photograph and its impact on six men, one photographer and an entire nation.

Photo Credit: HOF Inductee: ©Edward Burtynsky

Join Our Mission.

Joining the International Photography Hall of Fame is an unparalleled opportunity to immerse yourself in a global community of passionate photographers and enthusiasts. As a member, you gain exclusive access to a wealth of resources, including workshops and networking events designed to inspire and elevate your craft.

By joining us, you become an integral part of our mission to celebrate photography's artistry, innovation, and impact on a global scale. Whether you're a seasoned professional or an avid enthusiast, your membership empowers you to connect with like-minded individuals, explore new perspectives, and contribute to photographic excellence.